Hiking in Jabal Yanas with Marina Tsaliki

Marina Tsaliki is a botanist and has been doing extensive research on native and desert plants of the UAE with a focus on Ras Al Khaimah. We went to visit her to understand better the work she does and her research methodologies as a botanist. On the 20th of April 2021, we met with Marina, and she took us on a short trek in Jabal Yanas along the old donkey trail to look at the flora and the mountain species.

Nadine El Khoury: We are now at the top of Jabal Yanas in Ras Al Khaimah, UAE. When was the last time you surveyed this area?

Marina Tsaliki: I first started in 2011 and the last time I was here was a few weeks ago. My usual process is to allocate my 100 square meter plot and start looking for different species. But what I started doing now is I go back to places and just wander through because I’m still finding stuff that I didn’t see the first time around. Sometimes I know the area, and I check things, and then I recheck plants that I maybe had seen the year before, but I wasn’t sure about the identification. So, I go back to check again, and then I find that the goats have eaten all the plants.

NEK: Do you discover new species every year or is it more after the rainy period?

MT: I don’t necessarily discover new species or plants every year. Now that I know what the landscape is like, and the habitats, and I know the plants that are common in the UAE, so I know what to expect to see in different areas. So, I go searching for specific species as well. I heard of this plant in Shawka a type of small palm, which I had only found in one place. But I was told that there are loads of them. So I began to search, I went deeper into Shawka the mountain and into the other smaller wadies. And this year, so after three years of searching and fieldwork, I finally found more populations.

NEK: What do you do when you find new species?

MT: For me, let’s say I don’t want to lose any plants. If you only find one spot where you’ve got a specific plant species, you’re always worried that might get lost because of disturbances, construction, grazing, or whatever affects the plants. So, if you find more of them in different places, and the plants are doing well, it’s a bit like well, okay, so we’re not that at risk as I thought initially.

NEK: Okay. So that the natural environment is a bit more protected, or?

MT: If you find one population of something in one place, and you know that in the whole country you can’t find anywhere else, that alarms me. Because I’m like, well, we need to really take care of this area because we might lose it. And it’s just one plant, I understand that. But still, it’s part of an environment and everything plays its role in there.

NEK: Yeah, it’s an entire ecosystem.

MT: So, there you’ve got another village.

NEK: Are there a lot of like goat herders around here?

MT: Yeah. But the ones I’ve seen they’re all locals. So, the goats are owned by locals, but the herders as such…

MT: They often collect, like once this is done and more deserty, I don’t see them. They collect it for like fodder to use. I see them on the road sides collecting loads of it.

NEK: This is not a Samur (Acacia Tortilis), right?

MT: No, this is illicium. This is a plant species that grows all over regardless of its habitat. You can find it in the desert, you can find it in the mountain. So, it’s really very, very tolerant plant species of all sorts of environmental conditions.

NEK: Are there animals that like it?

MT: Yeah, they do. But it does grow a bit like bushy sort of like that. It’s got small like gray, green leaves, and the flowers are lilac white. And then it’s got bright orange berries as fruits, which are not edible.

NEK: They are poisonous?

MT: Well, yeah. In general, people often are like, can I eat this? Listen, in general, I wouldn’t eat anything unless I’m like 100 percent sure I know what it is, and I can eat it. I’m not a friend of, oh, let’s try or something, just don’t.

INEK: Animals smell and sense it.

MT: Yeah, they smell or sense it. But even some animals can eat plants that we can’t, and vice versa. We can eat things that animals can’t. It’s not like I came here and I [detect I have all these plants], others I have seen them before. This is not all my creation, or anything. People before have noted that this one is poisonous, or this particular plant is poisonous. So, I basically look it up. I go back, I check on a plant, look what [the book] says. So, my intention is just going back to the medicine. My impression from the meetings we’ve had so far, people use the plants for more external. So broken limbs or legs, twisted hands. Lots of plants are used for that. Ointments, skin issues, treats a lot of fever.

NEK: A lot of things are boiled and drunk as tea.

MT: Correct. For stomach, but hardly any of them are used for like really serious, I don’t know, cancer or things like that. I mean, all healers that you talk to know their limits, and they know when they have to stop. And when they have to send people to a proper doctor, or something like that.

NEK: So, it’s more like reducing inflammation, irritation, holistic kind of uses.

MT: Yeah. Lots of people, when you talk to them say it’s become harder to find the plants. Because with less rain, you’ve got fewer plants, we’ve got overgrazing and all of that. So, some of them struggle, and some of the plants they can’t find at all anymore.

NEK: But also, within that practice of herbal medicine, sometimes the roots are used in the preparation of remedies. So then, also uprooting from plants sometimes plays a role in it becoming an endangered species.

MT: Regarding roots, a lot of things we eat are roots, ginger, turmeric, onions, and garlic, it’s all the bulbs and everything that grows underground. And what I’ve noticed, is that with the local names, often they give a group of plants, I know that they have different names because they are different species. But they give this group one name. So, for instance, we’ve got the Pulicaria, the one where you said the wide flowers. This one is a relative to…

MT: We just passed by the greyish one there, is the same genus as both Pulicaria, but it’s two different species. In Arabic, they give it the same name. So, they don’t differentiate as much.It’s often detailed. Let’s say, there are some grass species where you’ve got five of them, if you just look at them like this, you won’t recognize a difference. But as a scientist, you know that you have to look at the seed and the bends on and if it bends like this, or if it’s straight, or if it’s not there.

NEK: So, also the seed is very important.

MT: Yeah. It’s often the seed that helps you identify or keep plants apart. Let’s say the fruits just look a bit different. You’ve got some plants that have beaks for instance, and they look exactly the same, only that one beak is five centimeters plus and the other one is shorter than five centimetres. So, things like that.

NEK: But that’s beautiful.

MT: It makes life difficult if there weren’t seeds. That’s why working on a seed bank becomes really important. And the more you know variety of number of seeds you have, the more I find that it’s such a fascinating but also really important endeavor, because these seeds are what’s going to stay.

NEK: Can you tell us the number of seeds you’ve collected so far, or is that private information?

MT: I can’t tell you the number, I can tell you we’ve collected about 50 species. Seed amounts are still quite low because I’m collecting all on my own. There’s just a limit to how much I can collect. But also, it’s the population size. I would never remove all the seeds of one population because I want the plant to survive. But for the seed bank, I will definitely get in touch with the guys at the Sharjah Seek Bank. They’ve got a lovely lab, they can show you the whole process of how they collect, how they dry, how they document and classify plants

Let’s get back down now.

My seed bank is a fridge and freezer. And me filling envelopes with seeds, giving them an accession number. Look!That’s the other Pulicaria. So that belongs to the same genus of the plant we saw earlier. But it’s different species.

NEK: The colour is different.

MT: Yeah. That’s a bit flashier and sort of a bit soft. It’s got the hairs to protect it from the sun. So, the guys in Sharjah, they have more like a proper lab and a fancier setup, let’s put it that way. And then there are really amazing seed banks, the Millennium seed bank in Kew. And in Norway, they’ve got another ginormous seed bank, the Svalbard global seed vault. Kew has this plan to collect seed samples of all of the plants of all over the world as a long term project. So that’s like your futuristic bank. But I’m not going to show you my seed bank. It probably doesn’t even deserve the name seed bank. But you have to start somewhere. And we started growing some of the plants in the nursery, some of them are coming up. For me, it is just these small things.

NEK: Is the nursery accessible to the public, or not?

MT: No. I’ll take you there later on. It’s again, a very small, it’s not a nice, fancy nursery. But I can show you some of the natives that we’ve just started growing. They’re like this, so you can’t tell what they are. But it works.

NEK: Also, just to go back to this idea of the seed bank, it’s not really about the facility, or the size of the thing. It’s more about like the seeds and the variety, and what you’re actually collecting, right?

MT: Yeah. I think like we here in RAK, we’ll probably have once in the future, one of the most diverse seed banks, because we’ve got the high mountains and we’ve got these habitats on high elevations that other emirates don’t have. I mean, of course, you can share. It’s not like it’s ours or anything. But just from what we can provide, I think we will be one of the most diverse.

NEK: But also, there’s the mountain and then there’s the coast. You have that whole range. So, are you planning on going down to the coast?

MT: We’re collecting as much as we can. At the moment, we go somewhere, wherever we see we take it. You also don’t just collect from one place one species, you have a species, you’ve got 10 other places, you go there and collect as well. Just to have diversity.

NEK: Let’s say you want to take a sample of a plant; do you take the plant or do you cut out a bit and then you grafted later? How do you sample a plant?

MT: Okay. It depends what I need it for. If I need it for herbariums, let’s say for an herbarium specimen. So, you know the sheets where you’ve got the full plant, identify it. Then you would take a piece of the plant, unless you’ve got like 30 kilometers, or like you’ve got a massive population and pulling out the entire plant doesn’t really matter. Like with grasses, you can do that easily. That’s not a problem. But here, I wouldn’t do it. I would take a piece where I’ve got leaves on it, where I can see how the branches are like, how the branching works on the plant, and ideally with a flower on it, or fluorescence. And then later on, I would come to get a piece of the fruit. Because you need all the pieces for identification, to be able to identify exactly what it is. And for later on people can compare what they’ve collected. And they say, oh, yeah, that’s that because of the fruits or look at the flower. If you’re collecting for propagation, first of all, it depends on the type of species.

NEK: Some can’t, like you can’t really graft.

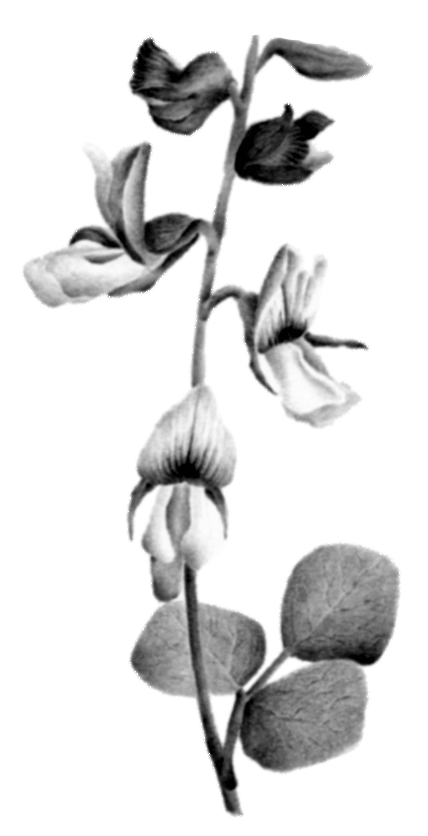

MT: Correct. What works at the moment, actually quite well is just taking cuttings. And there are different forms of cuttings, like heel cuttings or nodal, and internodal cutting. So, we’re trying all the different variations, and just testing which one works the best for semi-woody or woody species, the soft ones you do it with seeds usually. But then again, acacia trees, you would never take cuttings, no point. Take seeds, works much better. Cedar, exactly the same. Raftery, the same. Seeds just work super well.

NEK: And how does the seeds look like for different plants? Sometimes they’re obvious, they’re just like kind of hanging sacks and you see the seeds. And other plants are like, are they in the flower once it dries up it becomes like basil? It’s clear. It’s like where the purple flower is it dries up. And you take that and you plant and get another one. But then for desert plant, how do their seeds display?

MT: It really depends on the species, like what you’re looking at. So, for instance, lots of plants have, you’ve got the flower. And what’s at the bottom of the flower is actually what turns into the fruit and what includes the seeds. So that’s the bit that matures. And then that’s the bit you take and you’ve collected. When you can easily remove something from the plant then it’s ripe and mature. If you really have to like, or it’s bright green or something like that, it’s not ready yet. Plants like Tephrosia Appolonia, have pods, and they look like beans. And you just have to collect them before they burst open and you lose everything. It really depends on the plant species. Should we go on a little bit more?

NEK: Yeah, we can. Can you tell what that is?

Respondent: It’s a helianthemum, I think.

Interviewer 1: One flower.

Interviewer 2: It’s pretty big one.

Respondent: Yeah, this is again a different one. It’s got really beautiful. So, this one has hardly any leaves and the leaves are further inside. And the branches are like zigzag formed. It’s usually got like bright yellow flowers.

Interviewer 1: Yeah, I see one.

Respondent: Is there one? Oh, no.

Interviewer 1: No, it’s not? It’s from somewhere else?

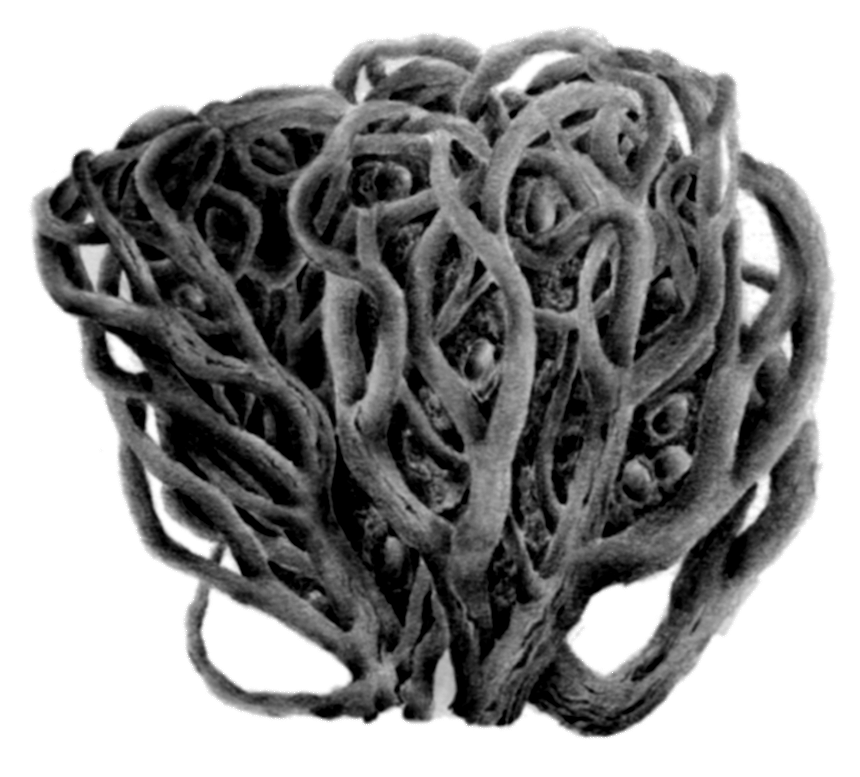

MT: This thing here is a hemiparasitic plant. it’s a plant that sort of connects to other plants, and they take like nutrients or something out of them. Like they don’t harm each other, but they need each other like for stability or nutrients or something like that, because they can’t reach into the ground or whatever. On the mountains, we’ve got cuscuta. This is this one.

NEK: So, this gives this nutrients?

MT: No, it’s the other way around.

NEK: It’s like a natural companion. How is it attached?

MT: They’ve got like tendrils where they just like, or they grow like a twining sort of growth structure. So, they just wind around the things.

check what happens here

Interviewer 1: I guess when it rains this would all be greener, or maybe just under kind of [indiscernible 00:26:29].

MT: What happens with the rain, especially on these dry soils, it runs off quite quickly. That’s also why the locals made these terraces you see in the distance, first of all, to capture some of the water, and then just to slow down the runoff. So that the majority of the rain would actually stay on their fields or on the terraces, only have a minor loss. All of these shrubs would be greener. But it wouldn’t be like a lawn or anything.

NEK: I’m fascinated by how many there are.

MT: But I guess it’s not really grazed that much, I guess goats don’t really like it.

NEK: Since we started our hikes and now, we’ve seen like seven different species at least. Am I mistaken?

Respondent: No, no, you’re right. And I’m not even really like taking a good, good look.

Interviewer 1: There was that one with the little flower.

Interviewer 2: It’s amazing how these plants can survive on almost nothing.

MT: Marina, this is also a part of our project, is to look at the biodiversity of the different areas of the UAE.

NEK: I wonder who made this trail?

MT: This is one of the old donkey’s trails when they transport food supplies and everything to the villages at the top of the mountain.