Accessibility

Black & White

High Contrast

Text Size

Cursor Size

In conversation : Shahina Ghazanfar with Namrata Neog and Nadine El Khoury

In conversation with Shahina Ghazanfar, Nadine El khoury and Namrata Neog.

Shahina Ghazanfar (lives and works in Cambridge, UK) is a botanist who has pursued research into plant taxonomy and conservation on four continents. She has contributed to the Flora of Pakistan, authoring many plant families in Pakistan. As an associate professor at Sultan Qaboos University, Oman, she conducted extensive in-country fieldwork that led to publishing the four-volume Flora of Oman (2003-2018). Her work extends to practical applications, with the Handbook of Arabian Medicinal Plants (1994: CRC Press) and various papers on medicinal plants of the Middle East. Her work at the University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji, resulted in Trees of Fiji (2006; co-authored with G. Keppel) and distance teaching to five Pacific nations. In 2001, she joined the staff of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, as co-editor for the Flora of Tropical East Africa (2008) and later as editor of Flora of Iraq (2017). At Kew, she developed collaborative projects in seed banking, restoration of damaged landscapes, use of native plants for landscaping, and capacity-building in the Arabian Peninsula. She is an accomplished natural historian and field naturalist with a distinguished publication record. In 2021, she received the prestigious Linnean Medal for botany.

NEK

Shahina, you have done some amazing work on the plants and biodiversity of the Gulf and Arab region. Your book The Arabian Handbook of Medicinal Plants (1994) is a fantastic resource and archive for people researching the region’s biodiversity. In your book, you recorded many medicinal uses of these plants from different communities and countries, including the UAE, Oman, and Yemen. I’m curious whether you also recorded rituals practicably practised in the different villages you visited. Did you collect this kind of information when you did fieldwork, or was this not common then? Did you go with anyone from the village for any foraging trips in the landscape, specifically searching for any of the plants on the list? If yes, why were they foraging specifically for those plants?

Shahina Ghazanfar

When it comes to rituals, it was more about the tradition of it rather than healing or finding a cure. Anastatica hierochuntica, of which Kaff Maryam is an example, has a distinct state when it dries. And they didn’t say it had a medicinal value, but they said that there’s a ritual and a sort of legend attached to it, that the Virgin Mary held it in her hand when giving birth to Jesus. That is a well-known story, and it’s mentioned also in some of the biblical references, though I’m not absolutely sure. So, drawing on the legend or the myth that is attached to it, it is used medicinally as well. It’s soaked in water, which women then drink to ease childbirth. There is no actual scientific proof that it helps chemically, but that’s what people believe in. Apart from that, there weren’t any other plants I encountered that were grounded in myth or folklore. I’m sure there are plenty, but I haven’t encountered them.

NN

Did you go with anyone from the village on any foraging trips, specifically in search of any of the plants in the list? If yes, why were they foraging specifically for those plants?

SG

I haven’t been with any villages as such because my intention wasn’t just to look at medicinal plants. That wasn’t my intention when I started collecting plants in Oman and in the Gulf States. It was meant to be a comprehensive collection of all plants so that we could get a list of the plants that were found in a particular region and, eventually, the whole country. But there wasn’t any particular foraging trip as such.

But whenever I did go, and I did go throughout the country and also throughout the UAE, and if there happened to be villagers who were there and saw me collecting plants, they would always make a small contribution. They’d ask me why I was collecting a certain plant, and I’d say, “This is for teaching purposes or my collection for the university,” which was very well respected.

And if they knew anything about the uses of certain plants or if they were used in a particular region, they would always share their knowledge. The one I gave you last time, for example, was Za’atar from the mountains of Northern Oman. It’s thyme, which they do use, and they would say, “We use this plant for this purpose, or this plant for that purpose.” They’re very generous when it comes to sharing their knowledge.

NEK:

Did you chance upon any historical texts, archives, or visuals which mentioned any of the plants on the list?

SG

Many historical texts feature plants, and it would be great to shed more light on these. These plants are not just new medicinal plants or plants that have only been used in the Arabian Peninsula or in the Middle East, but which have been used by several others, starting from the cuneiform texts 2,000 or 3,000 years ago.

NN

Can you tell us more about the plants we have in our garden at the Jameel Arts Centre?

SG

You have the Salvadora Persica, also known as the toothbrush plant, which is also mentioned in the Quran. It was obviously used before that, as well, but I haven’t found out exactly how far back its use goes. It’s a local plant, and it’s very common, so I’m sure it’s sure it’s been around for much longer.

Calligonum comosum is another interesting plant, also called arta. It’s been used for a very long time, but again, I’m not sure for exactly how long, but it was used in Eastern Saudi Arabia quite nicely. They would powder the stem and leaves and mix it with honey, and they would use it to coat the inside of the goat bags. It used to be very common to carry water from one place to another using goat bags made of goat skin. These leaves and honey were used to coat the inside of these leather bags to flavour camel’s milk. Camel milk is quite salty, and so to flavour it, they added arta and honey. This was recorded in one of the literature.

Then, of course, you have the Hamra, which is used to bring fevers down. The only interesting thing that I found out about Hamra, which is Arnebia hispidissima, is that the first name of the genus, Arnebia, was given by Forsskal, a Danish plant collector who came to Yemen through Egypt. That was his first collection from this part of the world. He gave the name of this plant, Arnebia (Arabic for “rabbit”), from the common people who called it shajaret el arneb (the rabbit tree in Arabic), it was used in traditional medicine to bring a fever down.

But there are two or three other species of it which are found in Kuwait… Not hispidissima. Tinctoria. And another one., Its root, which is quite red, was used to make a reddish dye. I think the Bedouin might still use it.

Henna, of course, was very popular. It was possibly mentioned in the Quran. There is a little bit of a controversy regarding whether it is a henna or another plant. But it is certainly mentioned in the Bible. So again, it is of some historical importance, or it has a history, certainly.

NEK

I think Henna originally came from India but has been cultivated in this part of the world for thousands of years.

SG

Felh or Lasaf is another plant, also known as Capparis spinosa. Capparis has been known for a very long time, though under a different name: caper. It was first documented by the Sumerians some 4,000 years ago in the cuneiform texts. It was also mentioned and used by the Acadians, as well. Its use has also been documented in the Assyrian peninsula. It was mentioned by Dioscorides around 200 BCE, and again in the 12th and 13th centuries by scholars from Andalusia. Capparis has a very long history as a medicinal plant. Of course, we only now use it for the capers that come out of it, which are the buds of the flowers. But it has its own medicinal history, so to speak.

Then we have Rehan or Ocimum basilicum, which is a Mediterranean plant, but it is also mentioned in the Quran. It is now mostly used to help settle an upset stomach or digestive problems. You make tea or an infusion out of it, and you drink it. There’s a bit of a controversy because Rehan basically comes from a sweet-smelling plant, and it’s possibly Ocimum, but we can’t be absolutely sure.

NEK: The plants you gave already mentioned are usually found in semi-mountainous environments; what about sand dunes and plains?

In your artist garden you have Haloxylon salicornicum, or Rimth, which is a very useful plant because it’s quite salty. When I was in Oman 25 years ago or so, I visited one of the villages and they said that they used Rimth when they were dyeing clothes. The plant’s saltiness helps to fix the dye, so they would add the stems mainly, but also some of the leaves, as a mordant during the dyeing process.

It is also a plant that has been referred to in the Bible as manna. When the Jews were being taken out of Egypt, it is believed and they were in the desert of Sinai. They complained about that you’re giving us nothing good to eat, and God sent them sweet manna to eat. It’s not exactly clear what manna is. There are so many theories about what it could be. In the Bible, there are four or five plants that qualify as a manna. One of them was Haloxylon salicornicum which is an insect that exudes a sweet liquid, and that liquid was collected by the Bedouin. In more recent times, it was used as a sweetener to sweeten their milk or any other beverage. So there is speculation that this might be one of the plants that qualify as manna.

Then there is Shih, which is one of my favourite plants. It’s also known as Artemisia sieberi. There are several species of Artemisia, which can all be used to bring down a fever. You boil it and drink the water if you have a headache or if you’re feeling feverish. It’s considered to be a remedy for all sorts of conditions in Syria. There’s a popular saying in Arabic, “Don’t give your enemy Shih because you don’t want to cure them.” It’s a plant that is thought to cure everything. It also has a beautiful scent.

NEK:

The Handbook of the Arabian Medicinal Plants, how long did the project take and with which communities did you work?

SG

My project at the time was basically to collect plants. I lived in Oman for 12 years, working as a teacher, and one of the things I made sure I did was to collect plants from all of the different districts, both in Oman and the UAE, which is a neighbouring country with a very similar landscape, especially the gravel areas. But as I was collecting plants and gathering all the information about their medicinal uses, there was an incentive to put together a book on the medicinal uses for the Arabian medicinal plants, whether from Oman or any of the Gulf states. With that in mind, I started to look further. Whenever I was out in the field in places like Kuwait or Qatar, I would always ask the local population, “What do you use this plant for?” and then collated all of this information into this book. This is in addition to extensive documentation from libraries, from literature, and from the papers, so the book was as comprehensive as possible at the time it was published. It took a very long time to put it together. It was published in 1994, and I did all of the illustrations myself. It must’ve taken about five years to complete, maybe more. I’m starting another book now on the Middle East. God knows how long it will take, but I’m at it now.

NEK:

How did you decide which plants to illustrate or not illustrate in the book?

SG:

I wanted to illustrate every species mentioned in the book. However, I depended upon herbarium specimens because it was difficult to go out and collect a fresh specimen at the time. And if the fresh specimen was good enough, I drew from there. So you’ll notice that the illustrations are two-dimensional rather than three-dimensional, unlike the kind of paintings you come across in botanical art because they were drawn mostly from herbarium specimens, while others were drawn from photographs, which I then converted into pen and ink drawings. I also photographed some of the plants. Evidently, illustrations are crucial for the identification of a plant. So that was the idea behind it.

NN:

while doing fieldwork and other research did you come across any spiritual beliefs associated with these plants?

SG

Traditional medicine encompasses different health practices and spiritual therapies, and regarding the Arabian Peninsula specifically, the question was about the link between medicinal plants and spiritual beliefs. I did not delve into the spiritual beliefs, but I really wish I had, and I’m certain there’s a wealth of knowledge there. The only one plant that I know of, which I encountered in Sanaa in North Yemen, was Ruta, or rue, as they call it, which is a very bad-smelling plant. They would make little amulets out of it to hang them to ward off evil spirits. Citrullus colocynthis or Handal, which I mentioned earlier, was also used because it was bitter. So they would use that, again, to ward off evil spirits.

Myrrh is another plant commonly used in Oman. When you burn it, it emits an acrid smell. Sometimes, when they put goats in caves overnight, or to make sure if they’re young lambs, they add a small around it to keep them safe. Then they burn the twigs or stems of Commiphora wightii (myrrh), which is found in Northern Oman because they think the smell will repel the snakes in the area. That’s the only thing I know, which is not really spiritual, as such, but they must have a lot of beliefs, I’m sure. If you’re living in the desert or if you’re living out there, I mean, these things do happen. Yeah.

Most of my research and fieldwork was in rural areas as wild desert plants are mostly found in open landscapes because even when there’s a small village attached to it, the native flora can be prone to destruction. So, I would always be in open landscapes or in well-preserved areas, where I would often find the best populations of a certain species.

NEK

Why did you focus your research on the Arabian Peninsula and desert plants?

SG

My research was focused on these regions simply because I happened to be living there during that time. I’ve always been fascinated by the desert. The tropical areas never fascinated me because plants grew abundantly over there. No factors are limiting their growth. The only limiting factor in the deep jungles is light. And, of course, then you have these plants growing on trees, like lianas and climbers. Whereas in the desert, you have many limiting factors. The sun is very strong, the temperatures are high, the soil is very poor and salty, and there’s hardly any organic matter. There’s also very little rain. So all these factors, which are abundant in a tropical climate or environment, are completely lacking in the desert.

I was fascinated by how plants actually survive over here. How do they adapt to the environment to survive? So it started with that, being fascinated by the plants in the desert. And then, when you start looking at the plants, several other aspects come to light, like medicinal plants. People who live in the deserts use these plants for medicinal purposes, not just for food. That’s how I became interested in this area.

I was lucky enough to be teaching in Oman, which allowed me to travel throughout the country. I would later travel to the UAE, where I’ve visited most of the habitats, and then, of course, Qatar and the other Gulf States. Apart from Saudi Arabia, I think I know the Arabian Peninsula. I was fortunate to visit these areas quite extensively and to collect different plants from there, which, of course, increased my knowledge and passion in a way.

You’ve also asked me about the different environments in which some of the plants on your list can be found. Your list does encompass plants that are found in extreme sand deserts. Most of them are from the gravel plains or sandy deserts. I think there are just a couple from the mountains. So you’ve got a good selection of plants. I don’t see any coastal ones, which are found by the sea. It would be difficult for you to grow these except for Salvadora, which does come up to the coast.

In the sand dunes, you may come across Arta, or Calligonum comosum. It grows in complete sand dunes.

The Desmidorchis arabica on your list is very much a mountain plant. You will never ever find it in the gravel desert. Like khansour ( Carraluma Arabica) is definitely a mountain plant which is used medicinally, together with several others.

Periploca is another mountain plant. It grows on low mountain and low hillsides, where the altitude is not very high..

Capparis also grows on low hills.

All the others you have over here are basically from the desert. They grow in arid, sandy gravel plains, and are some of them found in wadis (valleys). They sometimes have water in them. The ones that grow on sand dunes depend entirely upon dew. The dew collects and gets soaked into the sand where they’re growing, and that is their sole water supply.

NN

I’m very amazed hearing you talk about all of this. I’m trying to imagine you back in the 1990s, a woman on her own. To go around these landscapes is quite incredible.

SG

Oman was one of those countries where women were free to drive, and women didn’t always wear the veil, not like Saudi Arabia. We thought the whole of the Arabian Peninsula was like Saudi Arabia, but Oman was not at all like that. in fact, the in villages don’t even wear a black abaya at all. They wear very colourful clothes. Normally, you would see them in zina which are tight-ish pajamas, in a way, and a shirt on top. They would also wear a very colourful scarfs.In the central desert, I have seen some women wearing masks. They always put on a sort of a face mask, which covers their forehead and their face.

So it was quite easy for me to talk to the women and to be with them and ask them any questions I had. They were there in the villages doing common work. They would be with their goats drawing water from springs or carrying it from one place to the next.

I usually travelled with my husband or my assistant, who was at Sultan Qaboos University. We would sleep in tents outside and get up in the morning, make breakfast, and collect plants in the area. My assistant was very good because he would press them, and there’s a fair amount of notes that you have to take during the process , so he would press the flowers and I would make notes.

NN

I was wondering about people’s approach more than safety because you are always travelling in rural areas. It’s never a city space. And mostly, there’s a chance that you’ll have to interact with women. Were there instances where you were maybe not allowed to talk or inquire about certain plants that you were interested in?

SG:

No, I did not encounter that. When they did ask, I would always say that I was working at Sultan Qaboos University which is very well respected.As soon as I mentioned that I was doing work for the university or that I was a member of the university, they were very welcoming and cooperative. Omanis, like most of the Arabs, are very generous, and they are very welcoming anyway. I was travelling in Yemen at some point with two German collectors, and we had to sleep outside because there weren’t any hotels nearby. There was never any incident in which I felt that I couldn’t talk to local people. We always said that we were from a university and that we were collecting plants for educational or research purposes, and they always were fine with that.

There was a beautiful village in Oman on the Jebel Akhdar range. You go through Wadi Mistal, and you climb up almost 2,500 meters to the village to it. It’s a very pretty village where they grow apricots. They cultivate all sorts of things. A lot of tourists would go there, and the villagers didn’t always like it. And, of course, these were visitors who would walk through their fields. And the villagers just didn’t like so many people coming in through that.

The road is very rough, so very few people came in. I have never experienced any animosity from the villagers, but later on, I heard that they got a bit annoyed at the number of visitors who would come through the village.

NN:

There is a very set historical understanding of the uses of these plants, which you’ve encountered over the course of your research, and how, over time, the same plant comes to have a new meaning in today’s contemporary world. So it’s no longer how maybe a lot of Emirati people might not be pickling a plant in the same way the chef from Norway is doing it in Dubai. It’s just one of the many ways that plants transform in meaning over time.

SG

Yes, of course. It would be interesting to see how different flora is being used for different purposes. That in itself would be quite interesting to see.

Grewia Tenax

الخزم

Khazim mainly grows in the Fujairah region. The plant is used as fodder for animals, and birds are attracted to the sweetness of the plant. Khazim is also consumed as a tea to treat low hemoglobin levels.

Khazim

الخزم

Khazim (Grewia Tenax) mainly grows in the Fujairah region. The plant is used as fodder for animals, and birds are attracted to the sweetness of the plant. Khazim is also consumed as a tea to treat low hemoglobin levels.

Al Hamra/(Kahal)

حشيشة الأرنب (أو كاحل)

Al Hamra (Arnebia hispidissima) is usually found between the sandy soil plains of Ras al Khaimah and Dubna, Fujairah. The roots of the plant were used as a dye for clothes, as well as treated fevers by boiling the roots in water, and drinking as a tea. Its flowers and leaves are also loved by grazing goats.

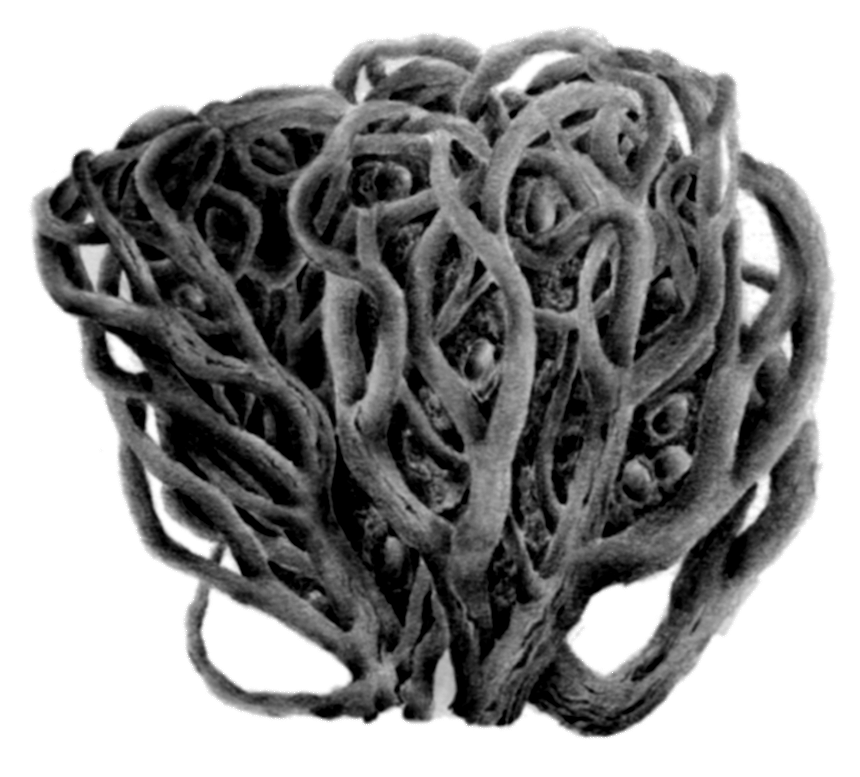

Kaff maryam

كف مريم أو شجرة العوار أو القشعة (عشبة الرهبان\شجرة إبراهيم\أصابع العذرا\شجرة العفة\عشبة المدينة)

Flowering between February and April, Kaff Maryam (Anastatica Hierochuntica) grows throughout the Arabian Peninsula in dry, sandy and silt wadi beds. The plant is easy to identify when it’s dry as the curled branches resemble a clenched fist. The dried stems unfurl when soaked in water producing a tonic that provides several medicinal uses for pregnant women, including increasing milk supply, prevention of early miscarriages, balancing the body’s hormones, aiding the muscles of the uterus and reducing labour pain. It also increases fertility in women and reduces menstrual pain. Many folk stories surround Kaff Maryam, including the story of Mary clenching the plant in her hand when giving birth to Jesus.