Accessibility

Black & White

High Contrast

Text Size

Cursor Size

Seasons of Entanglements

by Lakshmi Nivas

In the course of tending to our goats in recent years, we have been consistently warned and forced to see beyond the human paradigm of visual sight to watch out for foxes concealed behind bushes or in ground-level holes. These words of caution have come from fellow cow and goat herders during the grazing season in a landscape that predominantly consists of privately owned rice paddy fields, transforming into commons after rice harvest. The grazing season roughly takes place from January until the onset of the monsoons in June. During this period, grazing ceases as the fields slowly become submerged under the monsoon rains. The insistence on seeing what the human eye cannot, such as a gaze from a fox hidden behind the bush on livestock grazing in the landscape, stirs something in the human psyche which fundamentally shakes the very individuated image of the human self. Selfhood is not just the domain of the human but rather a cascade of embodiments of every non-human thinking in any given landscape and in this, humans too are part of that perception. The connection between the gaze and perception and its direct or indirect links to other socio-economic structures that bind the herder and the goat holds significance. It matters because the fox is a predator for both the human and the goat. For the human, the fox attacking the goat is linked to the herder’s wider economic sustenance derived from goat rearing and protecting the herd is protecting the herder’s economic structure. On the same note, the goat is ultimately regarded as prey to humans, while the fox plays a dual role as both predator and prey to humans. At some point in history, goats, foxes and humans built an alliance of interdependency. Although the structures of interdependency transformed in different ways globally, some form of alliance continues. The human, indeed, is neither accepted nor rejected by the more-than-human. “…typically humans see humans as humans, animals as animals and spirits (if they see them) as spirits; however, animals (predators) and spirits see humans as animals (as prey) to the same extent that animals (as prey) see humans as spirits or as animals (predators). By the same token, animals and spirits see themselves as humans; they perceive themselves as (or become) anthropomorphic beings when they are in their own houses or villages, and they experience their own habits and characteristics in the form of culture” (Eduardo Viveiros de Castro notes in his brilliant studies of Amerindian cultures). The gaze of the non-human on the human and vice versa quintessentially establishes the foundation of the complex dynamic called entanglement, embodiment and embeddedness of a landscape. At the same time embodiment of multiple perceptions transpires not just within inter-species entanglements but also towards the wider horizon of plants, seasons, rain, heat, wind and so on.

During the grazing season, the negotiation of the gaze sometimes occurs through the calls of our fellow herders, resembling animistic sounds, or through the entire herd collectively staring into the distance, followed by calls from the cows. The fox indeed contemplates the theatre of signals and calls. This is an emergence of what one might roughly call the politics and phonetics of language. When a language moves beyond the confines of grammatical syntaxes and lexicons, sounds, gestures and calls attain anthropomorphic forms. This gives agency to multiple locus (both human and non-human) at any given time in a landscape, setting the dynamic nature of entanglements.

The grazing season is also a peculiar period for dreaming. Many nights we wake up with false alarms triggered by dreams of foxes howling behind the goat shed, the anxious bleats of the young goats whose feet might have got stuck between the floor planks of the goat shed or quite often the visuals of dead goats in the morning possibly bitten by a snake at night. These lucid dreams are Freudian and animistic or totemic at the same time. They are lucid not because they emerged from any events of the previous days but rather as “dream distortions”, which ultimately become “wish fulfilment”. Drawing from an analogy of the self, the centralities of our psychic processes are also closely interlinked with the wider contemporary capital consumerist world we are part of. In a way one could almost say an existence of dualism between two worldviews and practice. These dreams hold significance as they symbolise an economy or sustenance reliant on maintaining the goat population, preventing it from dwindling due to attacks from foxes, snakes or accidents occurring within structures (goat sheds) we designed. These unpleasant “dream distortions” are a process towards “wish fulfilment” quality in the lucidity of dreams, which ensures we take steps to reduce the economic setbacks when the herd numbers are minimised. Simultaneously, these dreams resist being merely visual; phonetics is of particular importance and the sound of each animal needs to be paid attention to. The sound of the fox, goat or cow transpires in meanings to the herder in different times and seasons and hence a cacophony of toads and frogs in monsoons, as well as dreams of howling foxes behind goat sheds are directly related to the contemporary consumerist psyche of the human. Predation and prey, gaze and perception is not a stagnant entity but is a dynamic whole whose value and traction changes with relation to time. In navigating this, how does a contemporary human navigate the challenge of embracing multiple interconnected worldviews, most often dangerously unified?

Here we will take a slight detour from the self analogy towards an entanglement with the wider collective of the human selves. There is a product (let’s say a bar of soap), and then there are the related pertinent questions of provenance and process. In relation to that there is a self in the collective and the collective in the self, and there shall be the related questions of provenance and the process of individuation of the self. In this, the self and the collective is almost interchangeable. Between the product and the self lies a veritable bed of psychoanalytic processes, intricately involving time, space, memory, dreams, desires and perhaps guilt – skillfully incorporated and shockingly universalised in what could be called the contemporary consumerist world. The product, the self and the collective today is strangely entangled in this capitalist landscape. And in this landscape, animals, plants, horizons, seasons, rivers, mountains, deserts and so on have disappeared from the embodied dreams and myths of the contemporary human. At the same time, ironically and subconsciously, this product (the bar of soap/any object of mercantile exchange) is deeply embedded, individualised and collectivised within the contemporary human psyche of desire rather than with an embodiment and embeddedness of a non-human cosmology. At this intersection of time and space, it is of pertinent need to ask what does it mean to be a human in a post-industrial capitalist environment in the face of concretised dualism between the human and non-human, between human and ‘nature’ and between ‘nature’ and ‘culture’. Is it possible to repopulate and rethink our relational identity with the wider horizon of animals, plants, mountains, deserts, oceans, rivers, seasons? Can ‘nature’ as we understand it today move beyond its position as a backdrop for utility or aesthetic or recreation towards an embodiment within human psychic processes?

Before the rupture of the industrial world, animals, plants, seasons, mountains, rivers, oceans, lakes, deserts, and forests constituted the first circle of the human world. This centrality of the non-human world implied the absence of a dualistic separation between humans and animals or plants, consequently leading to the non-dualism between ‘nature’ and ‘culture’. Relations and identities transpired in a continuum that we today define as ‘social’ or ‘cultural’, and this continuity encompassed the entire non-human cosmology in any given environment. “Humans, I argue, are brought into existence as organisms-persons within a world inhabited by beings of manifold kinds, both human and non-human. Therefore, relations among humans, which we are accustomed to calling ‘social’, are but a sub-set of ecological relations.

….Ways of movement, and subsistence in the landscape give us a peek into the complexities and dynamics of the entanglement with the non-human and the wider environment while also reflecting a worldview comprising of myths and beliefs of a particular locale, in this locale comprising of innumerable engagements with the landscape; human and the nonhuman. Ways of acting are also ways of perceiving the environment.” (Tim Ingold in The Perception of the Environment)

It is on these intersectional and conflicting grounds that Desert is a Forest continues to evoke and grapple with the broader questions that influence the psychic processes of the contemporary post-industrial human. While Desert is a Forest focussed on the indigenous plants sourced from the deserts, mountains and wadis of the UAE, the approach is quintessentially animistic rather than naturalistic. Its animistic nature lies in its emphasis not on the singular aspects of plant taxonomy, morphology or uses alone, but rather on the need to contemplate a relational identity and meaning with the entire non-human/human cosmology as a whole in entanglement with the plants of the UAE environment. This highlights the historical significance of a landscape traversed over centuries by pastoral nomads with herds of sheep, goats or camels while also embodying the vast horizon of the non-human. It brings into consciousness the fact that pastoral nomads and seasonal farmers perceived and negotiated the same non-human cosmology of this landscape. Eating and seasonal migration was closely intertwined with seasons, water, mountains, wind, plants, foraging and so on. In such a mindscape/landscape, there is no distinction between human and nature. Hence, Desert is a Forest is not naturalistic because naturalism, as a school of philosophy, emerges from the Western modern perception that dichotomises human and nature or nature and culture without acknowledging the existence of innumerable worldviews where such distinctions do not exist. This naturalism has succinctly homogenised the (human) collective as opposed to ‘nature’ and is meticulously achieved by the capitalist structures whose existence depends on this very ‘nature’, elements of it today have become objects for the sustenance of human subjects. The ‘climatic’ consequences of which are burgeoning every day at devastating scales. How does one grapple and rethink towards a paradigm of a non-dualist world? While there is an urgency for future urban spaces to “rewild” with food forests or common rooftop edible gardens, will the post-industrial human ever comprehend what it means to have non-hierarchical relations with plants, animals, or the landscape as a whole?

Desert is a Forest is an attempt to push for a philosophy beyond the human, encouraging thinking along the lines of embeddedness, entanglement and embodiment of a landscape. It aims to understand agency in the selfhood of the non-human, working towards repopulating our mindscape with animals, seasons, time, history, grazing and blurring the lines between “nature” and “culture”.

Reference

Asad, Talad. 1970. The Kababish Arabs: Power, Authority and Consent in a Nomadic Tribe. London: C.Hurst & Co Publishers

Berger, John. 2009. Why Look at Animals? London: Penguin Books

Descola, Philippe. 2013. Beyond Nature and Culture; Translated by Janet Lloyd. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Freud, Sigmund. 2006. Interpreting Dreams; Translated by J.A. Underwood. London: Penguin Classics

Kohn, Eduardo. 2013. How Forests Think : Toward an Anthropology beyond the Human. Berkeley: University of California Press

Ingold, Tim. 2022. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Oxon: Routledge

Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 1992. From the Enemy’s Point of View: Humanity and Divinity in an Amazonian Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

*Special gratitude to a dear friend and anthropologist Dr. Lakshmi Pradeep for her insights and feedback on the text

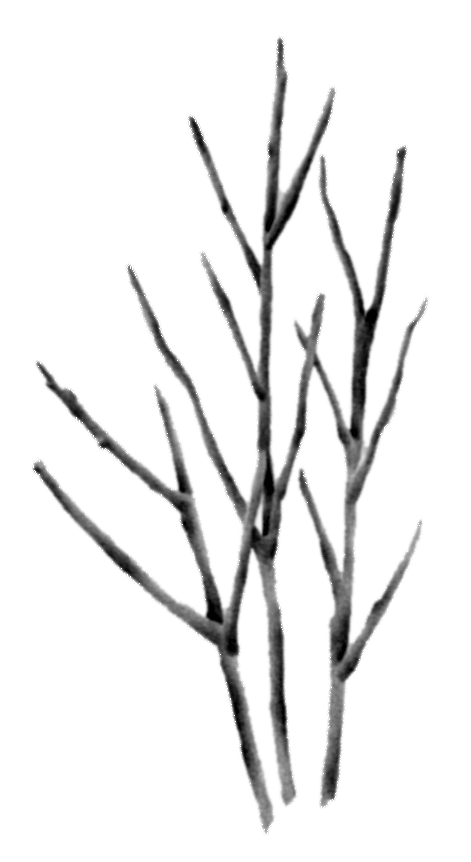

Grewia Tenax

الخزم

Khazim mainly grows in the Fujairah region. The plant is used as fodder for animals, and birds are attracted to the sweetness of the plant. Khazim is also consumed as a tea to treat low hemoglobin levels.

Khazim

الخزم

Khazim (Grewia Tenax) mainly grows in the Fujairah region. The plant is used as fodder for animals, and birds are attracted to the sweetness of the plant. Khazim is also consumed as a tea to treat low hemoglobin levels.

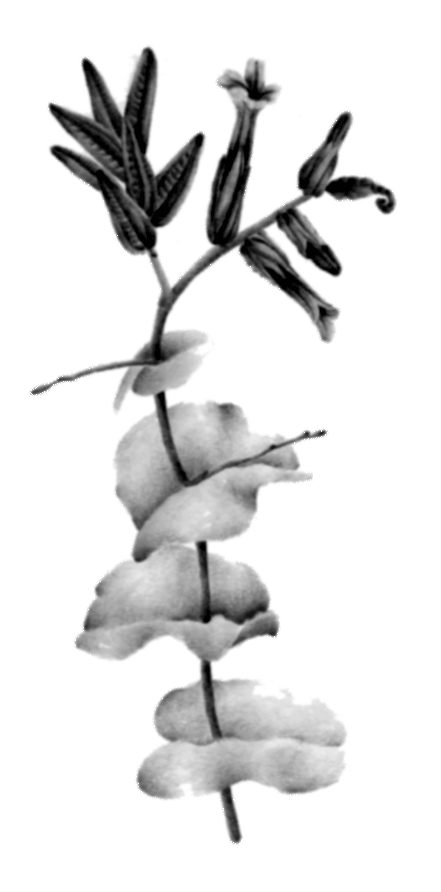

Al Hamra/(Kahal)

حشيشة الأرنب (أو كاحل)

Al Hamra (Arnebia hispidissima) is usually found between the sandy soil plains of Ras al Khaimah and Dubna, Fujairah. The roots of the plant were used as a dye for clothes, as well as treated fevers by boiling the roots in water, and drinking as a tea. Its flowers and leaves are also loved by grazing goats.

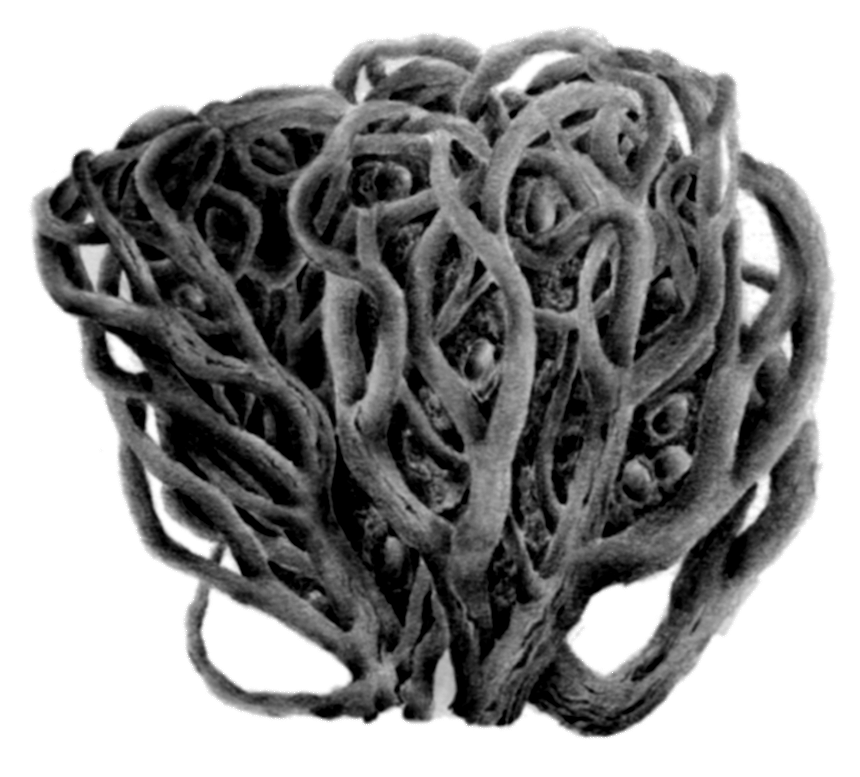

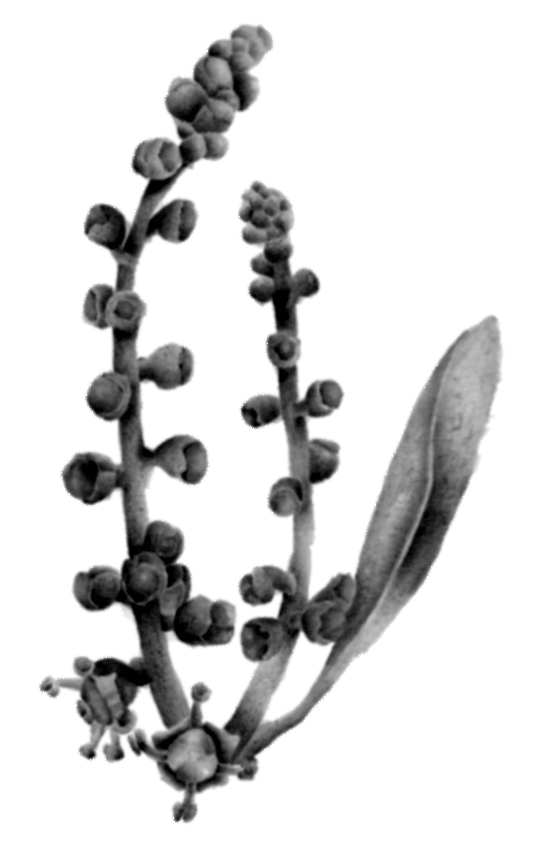

Kaff maryam

كف مريم أو شجرة العوار أو القشعة (عشبة الرهبان\شجرة إبراهيم\أصابع العذرا\شجرة العفة\عشبة المدينة)

Flowering between February and April, Kaff Maryam (Anastatica Hierochuntica) grows throughout the Arabian Peninsula in dry, sandy and silt wadi beds. The plant is easy to identify when it’s dry as the curled branches resemble a clenched fist. The dried stems unfurl when soaked in water producing a tonic that provides several medicinal uses for pregnant women, including increasing milk supply, prevention of early miscarriages, balancing the body’s hormones, aiding the muscles of the uterus and reducing labour pain. It also increases fertility in women and reduces menstrual pain. Many folk stories surround Kaff Maryam, including the story of Mary clenching the plant in her hand when giving birth to Jesus.

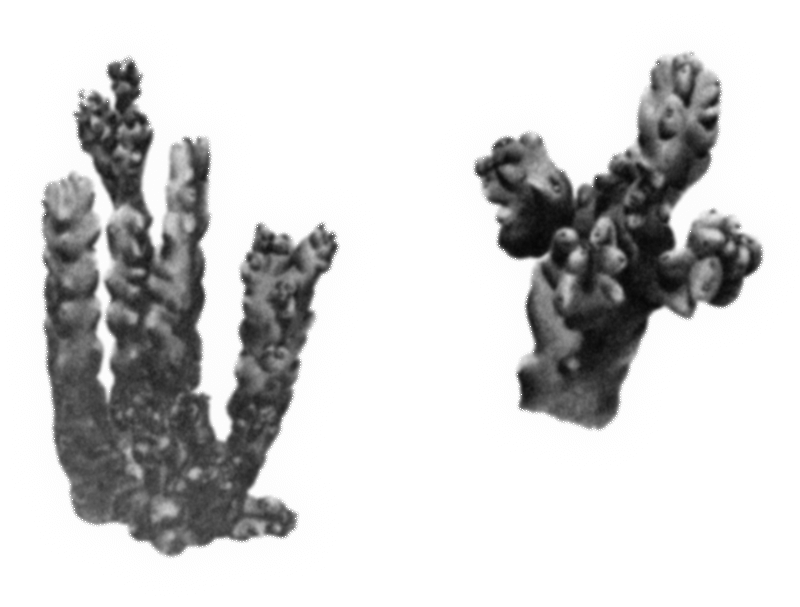

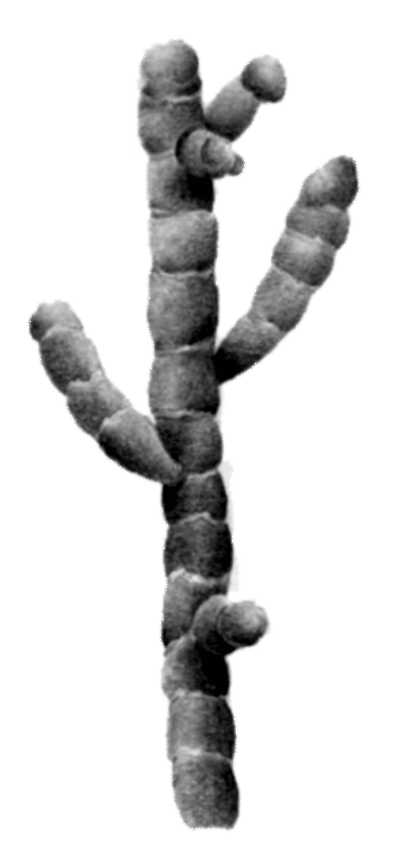

Thor

الظفر

Thriving in the valleys and mountains of Fujairah; goats, humans and birds are drawn to Thor (Tephrosia Appolonea) shrub for its seeds. People consume the seeds when they are still tender and birds consider this shrub as a safe haven for building nests.

Ghillih

أم لحلاح أو غلّ

Ghilih (Dyerophytum indicum) is a plant loved by humans and goats. Humans use the salty leaves as a seasoning for salads, and the fruits are eaten by goats.

Baql

الباقل

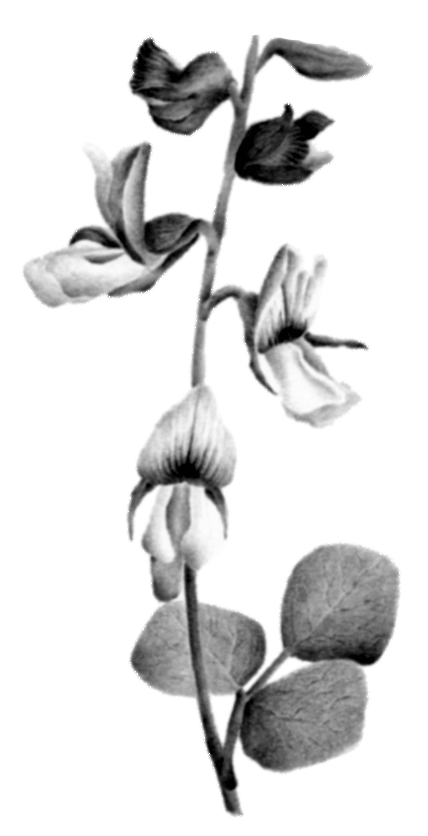

Baql (Rhynchosia minima) was once used as a substitute for coffee and is a common plant that grows across all parts of the UAE. It is also used in salads and as a garnish.

Khansour/Yadaa

الخنصور أو اليضع

Khansour/Yadaa (Desmidorchis Arabica) is mainly found in the high mountain ranges of the UAE. It often finds its way into Al Saloona, a meal eaten with rice, and the leaves are often added to salads. The plant also has medicinal properties, believed to help with diabetes. Commonly found with red blooms, the yellow bloom variant of this plant is now considered rare.

Hommed

الحميض

With a tang of sourness, Hommed (Rumex Vesicarius) is a plant loved by communities living around Ras Al Khaimah and Umm Al Quwain, especially when the plant starts blooming after the rain. Mostly eaten as a salad, this plant has two varieties – one which grows in the mountain or rocky areas and the other that grows in the sandy plains, difference only in colour and shape.

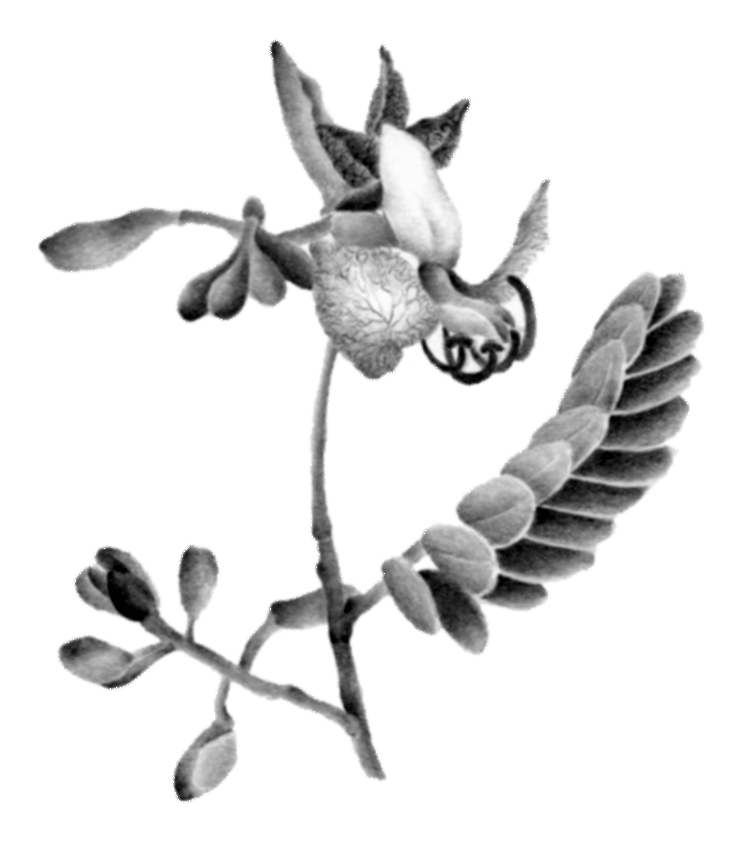

Markh

المرخ

Commonly widespread across the UAE, the tender leaves and flowers of Markh (Leptadenia Pryotechnica) were often used in different food preparations. Markh was also used to make rope and fishing tools. At the same time, it is a highly grazed plant by goats and other desert animals.

Maqarnah/Dahma

المقرنة أو دهمة

A small shrub that mainly thrives on sandy plains, Maqarnah (Monsonia Nivea) is often drunk as tea, prepared by drying the leaves and taken as a cure for fevers. Goats are drawn to the plants when they start producing flowers in January.

Sakhbar

الصخبر

Sakhbar (Cymbopogon commutatus) produces an oil that has a strong aromatic smell, and medicinal properties that protect against fever and is used as a diuretic when consumed as a tea.

Felh/Shaflah/Lasaf/Malat

الفِلح أو الشفلح أو اللصف أو شوك الحمار (القبار\الكبار\شرش القبار\ السَدير\عصلوب)

Humans and goats are drawn to Felh (Capparis Spinosa) at sunset, when the flowers open up and start blooming. The leaves of the plant are added to salads, and the flowers are used for preparing jam. The flowers are also known to relieve tooth pain.

Al-Raq/ِAl-Araq/Meswak

الراك أو الأراك أو المسواك

The roots of Al Raq (Salvadora Persica) continue to be used as a natural toothbrush in some parts of the UAE. It is a very important plant for goats and camels as it helps the animals produce milk, and gives their milk a high vitamin content.

Mohtadi

المهتدي

Mohtadi (Pulcaria Glutinosa) is used in perfumes and tea. It is also mixed with other leaves and salt to produce an ointment that is applied to wounds.

Rimth

الرمث

People in some parts of the UAE dry and grind Rimth (Haloxylon salicornicum) to add to boiling water as a tea, which is believed to be highly medicinal in nature. Goats also graze upon its spindly stems.

Seedaf

سيداف

Usually found across the wadis of the UAE, Seedaf (Pteropyrum Scoparium) grows in the winter, and the leaves are often added to salads.

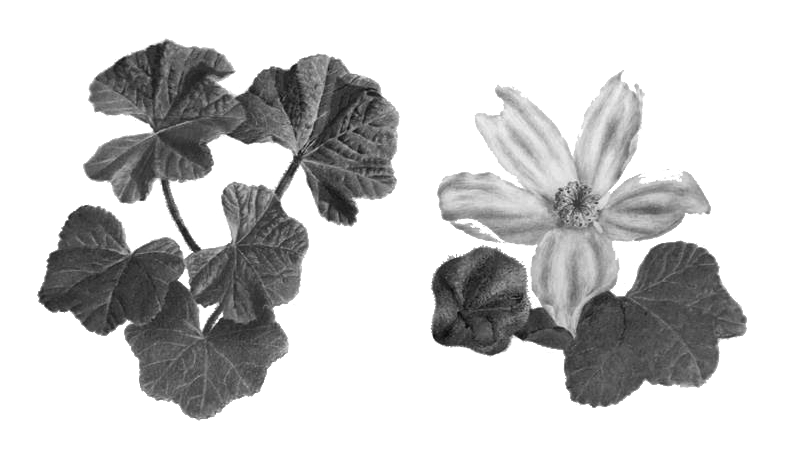

Khobez

الخُبيز

Khobez (Malva Parviflora) can be found throughout the UAE and is known to have a strong smell in the evenings. The leaves are boiled to make tea and added to salads. Khobez helps relieve stomach pain and cleanses the body.

Jadaa

الجعدة

A perennial aromatic plant that thrives in the mountain regions of the UAE. Characterised by different coloured flowers, Jadaa (Teucrium Polium) continues to be used in tea, sometimes as a replacement for mint and as medicinal concoctions for treating stomach pain (after being dried and mixed with either milk, water or juice). Traditionally, some of the flowers were used to make pillows as they remain fluffy with a mild fragrance.

Sobber

التمر الهندي

Sobber (Tamarindus Indica) grows widely in the mountainous regions of the UAE and is moderately tolerant to salt. It is often used as an ornamental tree in gardens and landscaping, and produces edible fruit. Goats also enjoy eating its leaves and fruits.

Ghoban/Sawas (Hindab/Attfa/Hallab)

الغوبان أو السواس

Ghoban (Periploca Aphylla) produces velvety dark red flowers that are used as a garnish for salads. The leaves are eaten by grazing goats.

Shih

الشيح

The Shih (Seriphidium Sieberi) leaves are used to make bitter tea, which helps relieve constipation, diabetes and was traditionally used to treat fevers.

Silm/Samur/Hardha

سلم

Common around Fujairah, Silm (Acacia hrenbergiana) is considered a rare tree. The yellow flowers of Silm are very special, as they attract bees and are used to make honey. The leaves are loved by goats, and as Silm is a thorny tree, it provides protection to the homes of birds and other small animals. Young leaves are used in salads as well as yellow flowers as garnish.

Rehan

الريحان أو ورق المشموم أو الحوك أو الحبق

Native to the Arabian Peninsula as well as Iraq, Syria and Lebanon, Rehan (Ocinum Basilicum L) is similar to basil. The leaves and flowers are added to salads and teas for flavour, and oil is extracted from the plant to produce perfume. The plant is also known for its medicinal uses, where leaves are infused in water and used as an expectorant to treat coughs and as a general tonic. Planted between March and April, the seeds can be propagated after two months of flowering.

Harmal

حرمل

Known for its medicinal properties, Harmel (Peganum Nitrariaceae) is used in traditional medicine for muscle pains, diabetes, stomach aches, wounds and cuts. Traditionally, the leaves were also boiled in water to bathe in, which helped relieve rashes and fungus on the skin. Goats also love to eat the flowers and leaves.

Rahel/Qataf

الرغل أو القطف

Rahel (Atriplex Halimus) is a unique plant that is naturally salty and used to season salads. It is also widely used as fodder for goats and camels.

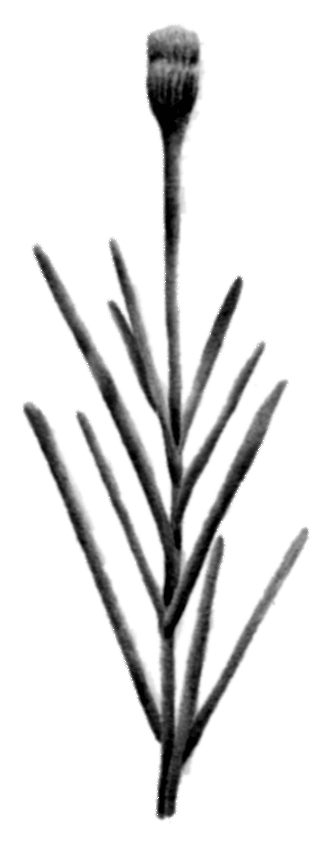

Hawa/Safara

حوة أو صفارى

Hawa (launacea arborescens) starts flowering in February. Goats wait eagerly for this time of the year to graze on the delicious flowers and tender branches.

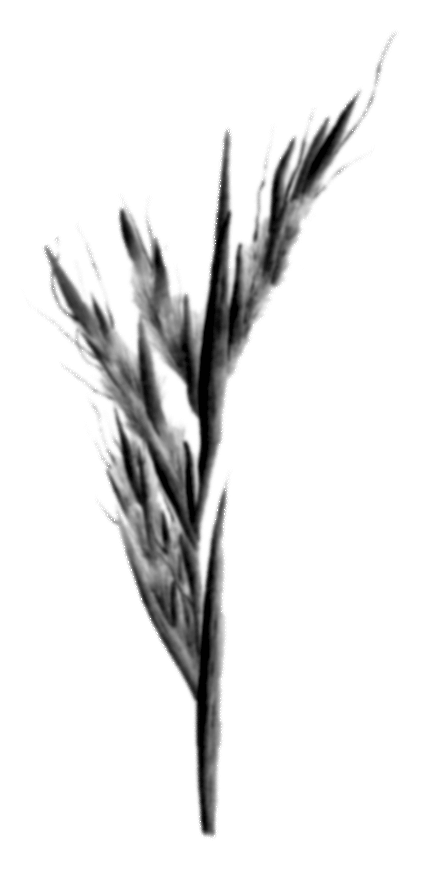

Thamam/Ithmam

ثمام أو إثمام

Thamam (panicum turgidum) seeds were once grinded and mixed with wheat to make bread. Today, goat farmers propagate the seeds and feed them to their animals. A barter economy also existed in the UAE, and the hay produced from Thamam was traded in exchange for wood and coffee.

Zaabal

زعبل

Zaabal (Triraphis pumilio) propagates by self-seeding and has a short lifespan of three months. Mostly found in the Jebel Hafit area, Zaabal is highly grazed by goats in this region, and is now considered a rare grass in the UAE.

Ghurayra/Sleisla

الغريراء أو سليسلا

Ghurayra (Eremobium aegyptiacum) is used in traditional medicine as a laxative and diuretic. This small bush is widespread across the UAE, from gravel plains to wadis, which makes it easy for goats to graze upon the plant.

Safrawi

الصفراوي

Widespread across the coastline of the UAE, Safrawi (Dipterygium Glaucum Cleome Pallida) has the ability to survive in saline sandy soils, and the fruit attracts a huge diversity of migratory birds and grazing animals, including goats. The plant was also used for traditional medicinal purposes, dried and drunk as a tea.

Henna

الخزامىالخزامى

Henna (Lawsoniainermis L) is one of the most commonly used plants in South Asia and many parts of the Arab world with a rich cultural history. The leaves are used to make a red dye that women apply to their hair and skin. Henna is also known for its medicinal and anti-inflammatory properties and was traditionally used as a local anesthetic for treating fever and mouth ulcers. Due to its high economic value, Henna is a widely cultivated plant in the UAE.

Arta/Abal

الأرطى أو العبل

There are two types of Arta (Calligonum comosum), spread between two diverse geographies – the ‘giant’ plant, growing in sandy regions, and the ‘small’ plant (arbi), growing in rocky terrains. Once the plants start flowering in March, people living in mountainous regions of the UAE add its beautiful bright red and yellow flowers, chopped leaves and soft stems into rice as a special dish. It is also during this time of year that the young shoots of the plant are collected and added to salads. The leaves of the plant are also used as a tea to treat diarrhoea, and often dried in the sun and infused in water or fish oil for cooking.

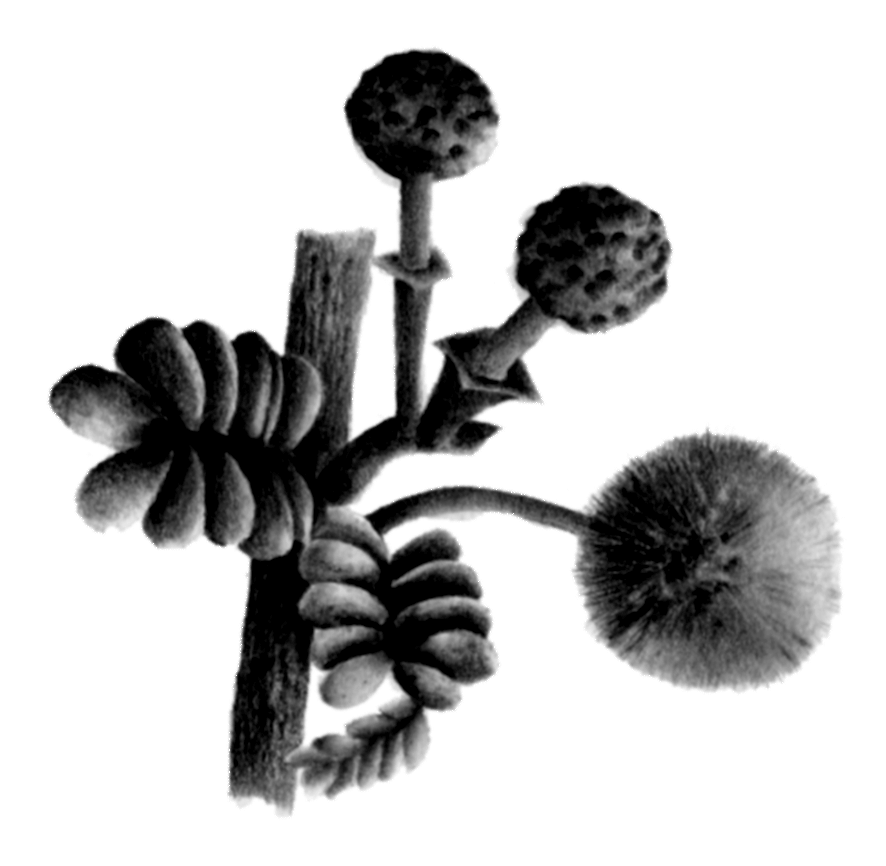

Arfaj

عرفج

Arfaj (Rhanterium epapposum) starts flowering in December. Historically, people ate the tender flowers by picking them off of the plants. Goats thrive on the plant, which nourishes their milk. Today, Arfaj is considered one of the rarest plants in the UAE and is mostly found in the north-eastern part of the country.